Implement racket/trace Like Observability Using eBPF

Background

I’m reading the new JavaScript version of SICP, there is an exercise about

drawing the tree recursion process, Exercise 1.14.

In the previous MIT Scheme version, we can use trace to print that flow.

It’s also available in Racket, can be used like this:

#lang sicp

(#%require racket/trace)

(define (fib n)

(if (< n 2)

n

(+ (fib (- n 1)) (fib (- n 2)))))

(trace fib)

(fib 4)

the output is:

>{fib 4}

> {fib 3}

> >{fib 2}

> > {fib 1}

< < 1

> > {fib 0}

< < 0

< <1

> >{fib 1}

< <1

< 2

> {fib 2}

> >{fib 1}

< <1

> >{fib 0}

< <0

< 1

<3

3

It’s very useful for understanding the recursive process. Unfortunately, it’s not available in most languages. I’m curious if we can implement something similar using eBPF. It turns out we can, but with some limitations. It’s easy for compiled languages like C or Go, but hard for JIT/interpreted ones like Java or Node.js.

In this post, I will show you how to implement a simple version of trace

using eBPF, and visualize the call stack.

C

Let’s start with C, rewrite fib:

#include <stdio.h>

int fib(int n)

{

return n < 2 ? n : fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2);

}

void main(void)

{

int n = 10;

int res = fib(n);

printf("fib(%d) = %d\n", n, res);

}

$ gcc fib.c -o fib

$ ./fib

fib(4) = 3

To implement trace, we need to know when a function is called and when it returns.

It can be done by using uprobe and uretprobe in

bpftrace.

Find function symbol in C

First we need to verify the function symbol:

$ objdump -t fib | grep fib

fib: file format elf64-x86-64

0000000000000000 l df *ABS* 0000000000000000 fib.c

0000000000001149 g F .text 000000000000003f fib

So fib is the one we want, as we expected.

uprobe in C

Trace the function call parameters using uprobe:

$ sudo bpftrace -e 'uprobe:./fib:fib { printf("arg0: %d\n", arg0); }'

Attaching 1 probe...

In another terminal, run the program:

./fib

The output of bpftrace is

arg0: 4

arg0: 3

arg0: 2

arg0: 1

arg0: 0

arg0: 1

arg0: 2

arg0: 1

arg0: 0

uretprobe in C

Trace the function return value using uretprobe:

$ sudo bpftrace -e 'uretprobe:./fib:fib { printf("ret: %d\n", retval); }'

Attaching 1 probe...

In another terminal, run the program:

./fib

The output of bpftrace is

ret: 1

ret: 0

ret: 1

ret: 1

ret: 2

ret: 1

ret: 0

ret: 1

ret: 3

Combine uprobe and uretprobe

Now we can combine them together:

$ sudo bpftrace -e 'uprobe:./fib:fib { printf("fib(%d) = \n", arg0); } uretprobe:./fib:fib { printf("%d\n", retval)}'

Attaching 2 probes...

fib(4)

fib(3)

fib(2)

fib(1)

= 1

fib(0)

= 0

= 1

fib(1)

= 1

= 2

fib(2)

fib(1)

= 1

fib(0)

= 0

= 1

= 3

It’s almost what we want, leave pretty visualization later.

Go

Can we do the same thing in Go?

First, rewrite fib in Go:

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func fib(n int) int {

if n < 2 {

return n

}

return fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2)

}

func main() {

n := 4

res := fib(n)

fmt.Printf("fib(%d) = %d\n", n, res)

}

go build fib.go

Find function symbol in Go

$ objdump -t fib | grep fib

fib: file format elf64-x86-64

000000000047f560 g F .text 000000000000006e main.fib

main.fib is what we want.

uprobe in Go

$ sudo bpftrace -e 'uprobe:./fib:main.fib { printf("arg0: %d\n", arg0); }'

Attaching 1 probe...

arg0: 0

arg0: 0

arg0: 8608

arg0: 8608

arg0: 8608

arg0: 8608

arg0: 8608

arg0: 8608

arg0: 8608

arg0: 8608

arg0: 8608

arg0: 8608

arg0: 8608

Oops, we got some unexpected output. Let’s do further investigations.

Disassemble the function:

objdump -d fib > fib.asm

Here are some highlights:

000000000047f560 <main.fib>:

...

47f574: 48 83 f8 02 cmp $0x2,%rax

47f578: 7d 0a jge 47f584 <main.fib+0x24>

47f57a: 48 8b 6c 24 10 mov 0x10(%rsp),%rbp

47f57f: 48 83 c4 18 add $0x18,%rsp

47f583: c3 ret

...

000000000047f5e0 <main.main>:

...

47f5f8: b8 04 00 00 00 mov $0x4,%eax

47f5fd: 0f 1f 00 nopl (%rax)

47f600: e8 5b ff ff ff call 47f560 <main.fib>

47f605: 48 89 44 24 38 mov %rax,0x38(%rsp)

...

If you are familiar with C ABI, you may notice something different here.

The first argument of fib is passed in %rax, not %rdi.

Go has a different calling convention than C, doc

here.

The amd64 architecture uses the following sequence of 9 registers for integer arguments and results: RAX, RBX, RCX, RDI, RSI, R8, R9, R10, R11

We can verify it using gdb:

$ gdb ./fib

(gdb) b main.fib

(gdb) r

(gdb) i r

rax 0x4 4

rbx 0x0 0

rcx 0x0 0

rdx 0x49de88 4841096

rsi 0x1 1

rdi 0x0 0

...

We can see that rax is 0x4, which is the first argument of fib, rdi is 0x0.

We can continue twice, then check again.

(gdb) c

(gdb) c

(gdb) i r

rax 0x3 3

rbx 0x47f5c7 4715975

rcx 0xc000186000 824635318272

rdx 0x0 0

rsi 0x0 0

rdi 0xc0000021a0 824633729440

...

rdi is 0xc0000021a0, if we grab the last 4 bytes, it’s 0x21a0, which is 8608 in decimal.

$ python3 -c 'print(int("0x21a0", 0))'

8608

You may get different values on your machine, but the idea is the same.

Now we solved mystery of arg0: 8608, how can we get the correct value?

bpftrace support reading register values using

reg.

$ sudo bpftrace -e 'uprobe:./fib:main.fib { printf("arg0: %d\n", reg("ax")); }'

Attaching 1 probe...

arg0: 4

arg0: 3

arg0: 2

arg0: 2

arg0: 1

arg0: 1

arg0: 0

arg0: 1

arg0: 2

arg0: 1

arg0: 0

arg0: 0

So the final command is:

$ sudo bpftrace -e 'uprobe:./fib:main.fib { printf("fib(%d) = \n", reg("ax")); } uretprobe:./fib:main.fib { printf("%d\n", retval)}'

Attaching 2 probes...

fib(4)

fib(3)

fib(2)

fib(2)

fib(1)

= 1

fib(0)

= 0

= 1

= 1

fib(1)

= 1

= 2

fib(2)

fib(1)

fib(1)

= 1

= 1

fib(0)

= 0

= 1

= 3

Note this only works for Go 1.17+, because Go 1.17 switched to register-based ABI, see here. For older Go versions, arguments are passed in stack, we need to use sargN to inspect them.

Trace-viewer

There are many tools to visualize the stack trace, like FlameGraph.

But there is one tool you probably already have, Trace-viewer.

It’s available in Chrome by visiting chrome://tracing/.

The supported trace event format is documented here.

We will use Duration Events for this example.

To include all info for trace viewer, the bpftrace command become a little bit longer,

so I put it in a file fib.bt:

#!/usr/bin/env bpftrace

uprobe:./fib:fib {

printf(">,%d,%d,%d,%d\n", arg0, elapsed / 1000, pid, tid);

}

uretprobe:./fib:fib {

printf("<,%d,%d,%d,%d\n", retval, elapsed / 1000, pid, tid);

}

bpftrace also support json output, so we can get trace using:

sudo ./fib.bt -f json > trace.jsonl

The file is like this:

{"type": "attached_probes", "data": {"probes": 2}}

{"type": "printf", "data": ">,4,4292644,3837,3837\n"}

{"type": "printf", "data": ">,3,4292918,3837,3837\n"}

...

To convert it to trace viewer format, we can do some python processing bpftrace2trace.py:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import sys

import json

def main():

result = []

for line in sys.stdin:

if line:

data = json.loads(line.strip())

if data['type'] == 'printf':

type, value, timestamp, pid, tid = data['data'].strip().split(',')

args = { 'arg0': int(value) } if type == '>' else { 'ret': int(value) }

result.append({

'ph': 'B' if type == '>' else 'E',

'name': f'fib({value})' if type == '>' else '',

'ts': int(timestamp),

'pid': int(pid),

'tid': int(tid),

'args': args,

})

print(json.dumps(result))

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Then we can get the trace viewer format:

./bpftrace2trace.py < trace.jsonl > trace.json

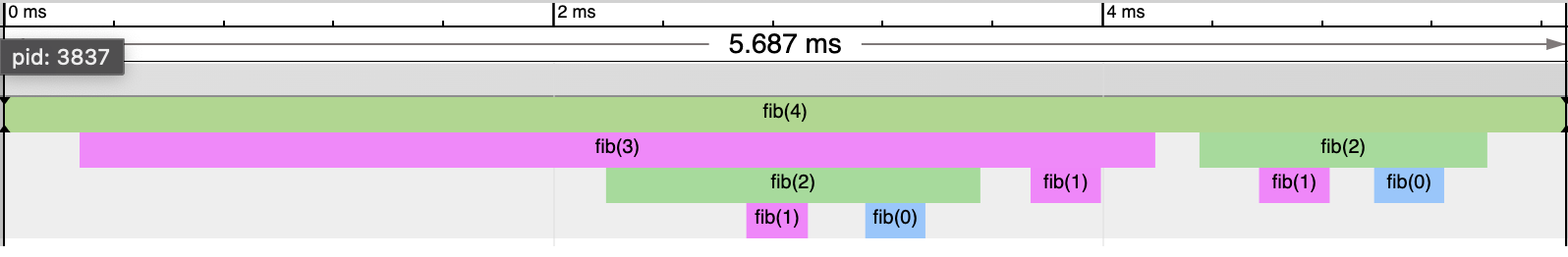

Load file in chrome://tracing/, we can see the trace:

Conclusion

With the help of eBPF, we can trace function calls without modifying the source code.

We only covered compiled languages here, and it depends on language specific ABI to work.

For other languages, uprobe or uretprobe may not work, there are other ways to trace them,

like USDT, but they require language specific support.

Chrome trace viewer is a handy tool to visualize trace, the format is simple and easy to generate. It’s a good addition to observability toolbox.

All the code for this post is available at this gist.